Originally published on AZCentral.com on October 21, 2016.

“Let me tell you what death is like.”

LeAnn Hull thinks teenagers have been desensitized to death by violent movies and video games. It’s not like what they see on the screen. She wants them — and their parents — to understand.

So she tells them about her 16-year-old son, Andy.

He was a left-handed pitcher who played varsity baseball at Sandra Day O’Connor High School in north Phoenix. College coaches were calling him. Major league baseball scouts were eyeing him.

Andy got decent grades. He was almost an Eagle Scout. He loved wakeboarding and snowboarding.

He was always cracking jokes and pulling faces. His teammates and friends called him “Sunshine.”

But it wasn’t enough for him. It didn’t matter.

On Dec. 11, 2012, after writing in his journal in second-period English that he was excited about the upcoming winter break, Andy got into his truck and left campus.

He stopped at Hong Kong Asian Cuisine, his favorite, for an order of spicy beef and chow mein to go. He took it home.

He closed the door to his bedroom. He watched a music video on his computer. Then shot himself in the head with a family gun.

What do you say? Start with, ‘You matter.’

It’s heartbreaking. And it is getting worse. The suicide rate for youth has risen steadily since 2007.Experts don’t know why, though they can guess. Untreated mental health disorders. Cyberbullying. Economic issues.

Last weekend, another teenage boy killed himself in Tempe.

The school sent another email to parents with suggestions about how to help their children through the death of a classmate. The first email was sent just a year and a half ago after another student at the same school fatally shot himself on campus.

I don’t know what to say. Not many people do.

LeAnn knows exactly what to say when a teenager completes suicide. She says it to the very kids who might be thinking about it.

In school libraries and gymnasiums, LeAnn tells teenagers what it is like to watch a game her boy should have been playing in and to leave afterward with no dust-covered son and no sweaty uniform to wash later.

She talks about who might be at risk for suicide. She talks about how to cope when things go wrong.

And over and over, she tells them, “You matter.”

Andy’s story

Andy was the youngest of four. His two older brothers were in the military and his sister was a nurse. He lived with his parents in a big house just off the Carefree Highway in north Phoenix.

Andy was the youngest of four. His two older brothers were in the military and his sister was a nurse. He lived with his parents in a big house just off the Carefree Highway in north Phoenix.

When he turned 16, his dad gave his son his blue Ford F-150 and bought himself a new truck.

Andy made the varsity team at school as a freshman. He was a natural, 6 feet tall and strong. And he loved the game.

At a game in October, a half dozen scouts were lined up behind the backstop, each aiming a radar gun at Andy as he pitched. LeAnn paced behind the bleachers.

Andy struck out one, two, three batters in a row and galloped back to the dugout, grinning.

‘Where could he be?’

LeAnn was at work, trying to finish up early so she could meet a cleaning crew at the house at 3 p.m. She glanced at the clock and realized she wasn’t going to make it.

So she called Craig Dean, a neighbor and friend, and asked if he would mind handling it. He was happy to.

Then she called Andy. She talked to him for a few minutes every day after school let out at 2:17 p.m.

But Andy didn’t answer. She waited a few minutes and called again. No answer. She left a message.

When Andy didn’t call back, LeAnn called one friend, but the friend hadn’t been to school that day. She reached another friend who told her he had seen Andy leave school early.

Her stomach twisted.

She called Andy’s coach. No, he wasn’t at practice.

LeAnn began to panic. “Where could he be?” she thought.

LeAnn shut down her computer and left the office. Just after 3 p.m., she turned into her driveway to see a Daisy Mountain Fire Department truck and sheriff’s vehicle.

She ran toward the house, but the deputy ran forward and caught her.

“Where’s my son?” she demanded.

“He’s dead,” the deputy said.

It was that simple. That final.

She collapsed and lay on the cold concrete. The deputy sat with her until she stopped screaming.

‘I’m not the first …’

When Craig had arrived just before 3 p.m. to meet the cleaning crew for LeAnn, Andy’s truck was parked in the circular driveway, the driver’s door open.

The front door was unlocked. Craig called out for Andy, who he had known since the boy was 8. He regularly went to Andy’s ballgames.

Craig had pushed open the door to Andy’s bedroom. He was on the floor, the fatal gunshot wound to his head.

Someone got LeAnn up off the ground and took her to a neighbor’s house. During the next hour or so, dozens of teenagers, some with their parents, filled the street.

Alone in the bathroom, LeAnn looked into the mirror and said out loud, “I will praise you in this storm,” a lyric from a song by the Christian band Casting Crowns.

Because it is easy to have faith when times are good.

And then she told herself, “I’m not the first mom to lose a kid.”

‘A special place in my heart’

In shock, LeAnn finally slept.

She woke at 4 a.m. Her daughter had waited for the restoration crew to clean Andy’s bedroom and leave, taking away the blood-soaked bedding and carpets.

And then Beth had painted a blue heart, 3 feet across, on the concrete floor to cover the blood stain that had seeped through the carpet.

When Andy’s friends came back, knocking tentatively on the door hours later, they lay on the blue heart on Andy’s floor, writing messages in marker around it.

“You will always have a special place in my heart.”

“You mean everything to me.

“I love you so much.”

In retrospect, LeAnn can see the warning signs. But she didn’t see them at the time. She never would have thought her son was at risk of suicide. Not her Sunshine.

Andy had broken up with his longtime girlfriend in the spring so he could focus on his schoolwork and baseball. Some weekends, he played as many as 10 games.

In June, he began taking a medication for acne that came with a warning of possible side effects, including depressed mood, trouble concentrating, changes in behavior and thoughts of suicide, among others.

Suddenly, Andy was having trouble concentrating in class and even remembering how to get to this ballfield or that one. He was struggling in English class.

Even now, it doesn’t seem like any one of these things was so dire. But there were other things that happened. Things LeAnn didn’t find out about until it was too late.

‘Let me tell you what death is like’

Four months after Andy died, there was another suicide at a nearby high school. The principal of Andy’s school asked LeAnn to speak to at an assembly.

It was hard to talk about what happened to Andy in front of so many people that first time. But she wanted them to know that no matter what happened, they were important. They mattered.

“I wanted to save someone else’s kid,” LeAnn says. So she started Andy Hull’s Sunshine Foundation.

Now she speaks at schools, conferences, hospitals, military bases, prisons — anywhere someone will listen. These are difficult conversations but necessary, she says.

She tempers each presentation for the particular audience, though sometimes she wishes she could be more graphic with the teenagers. She worries that violent movies and graphic video games have desensitized them to death.

It’s not like what they see on the screen.

“Let me tell you what death is like,” LeAnn says.

It looks like a blood stain on a concrete floor from a gunshot wound to a head.

It feels like holding her frozen son at the mortuary.

It is dipping into a bag of ashes, what remains of your youngest child, trying to figure out how to divide them among family and friends.

When LeAnn is given the chance, she tells parents to ignore the experts who caution them against being “helicopter parents” and tell them to give their teenagers privacy.

In the moments before Andy pulled the trigger that day, he watched a music video with violent lyrics — and copied what he saw on the screen. He had watched it before, LeAnn would later learn. She would have liked the chance to talk to him about it.

This is a volatile time for children, she will tell parents. “You’ve got one chance. You better hover over them. You better invade their space. You better know what their passwords to their computers are. You better be Tweeting. Don’t tell me you don’t know how to Tweet. You better figure it out. You better be on Instagram. You better be on Snapchat.

“That’s an amazing opportunity to see what’s really going on inside your kid’s head.”

No one wears a sign

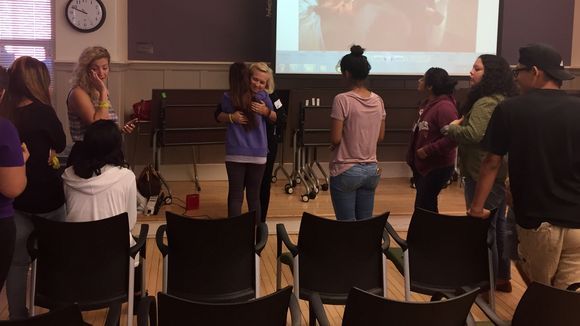

On Thursday, LeAnn was in the library at Bioscience High School in Phoenix, where she would speak to four groups of students, starting with the juniors.

On a big screen behind her, there’s a slideshow with pictures of Andy. Grinning in his baseball uniform. Flying in the air on a wakeboard behind a boat. In a shirt and tie with a beautiful girl at his side before a school dance.

This is personal for me, she says. Her son, Andy, the boy in the slideshow, died by suicide. The students are silent, listening.

She talks about who is at risk for suicide. How can you tell?

“No one wears a sign that says, ‘I’m thinking about suicide,’ ” she says.

The assumption is that it would be someone who is isolated — a loner — with trouble at home, someone who dresses in dark clothes and looks sad all the time.

She never would have thought her son was at risk of suicide. Not her Sunshine. She tells them

about Andy’s nickname, “Sunshine.” “When you were down or you were low, whether you had broke up with your girlfriend or struck out at bat, you could count on Andy to cheer you up.”

Not one person who knew Andy ever would have guessed he would complete suicide. It just didn’t make sense.

LeAnn talks with kids about how at this time in their lives, they are thinking about the future and imagining their successes. But they will experience failure, too. Maybe they don’t get into the first choice for college. Maybe a friend calls them a loser. Or their parents get divorced.

“How will you cope?” she asks.

There wasn’t one big thing that made Andy pull that trigger. It was a culmination of things. She tells them about the acne medicine, the college coaches and the scouts, Andy’s worries about his English grade and the break-up with his girlfriend.

Then she asks if they would be willing to let her look at their cellphone, at the last thing they posted on social media.

Because two of Andy’s friends had played a prank on him and captured it on Snapchat. It happened five days before Andy shot himself.

“They didn’t mean any harm,” LeAnn says. It was a joke. But what if something they posted on social media was just the thing to trigger for someone in a moment of pain to attempt suicide?

“Can you live with that?”

Coping, always coping

A month after Andy died, LeAnn learned that he had twice told friends, two different friends on separate occasions, that he had put a gun to his head.

Each friend made Andy promise he wouldn’t do it again — and he made them promise not to tell anyone.

This can’t be a secret: “You have to tell. Put the friend before the friendship.”

LeAnn admits that she thinks about suicide every day. Not only her son’s. Her own.

“I don’t just think about it. I plan it. I think about all the ways that I could,” she says. “I walk myself right up to that moment.”

LeAnn doesn’t tell the students this, but she has sat along Carefree Highway and weighed pulling out in front of a semi-truck. She has pulled into the garage and thought about closing the door and letting the truck run.

But she doesn’t do it. Because she has learned how to cope.

She reads a lot, not about suicide or depression but about other people who inspire her. She spends time with friends. Her circle now includes other parents whose children died by suicide.

She exercises, hiking and going to yoga. She meditates.

And she talks.

“It’s hard to be here. It’s hard to do this,” she says to the roomful of young people.

She takes a sip of water and lets out a long breath.

She presses a button on her phone and Dierks Bentley’s song, “Riser,” begins to play.

LeAnn looks up at picture on the screen behind her. And when she turns around, there are tears in her eyes.

“I miss that kid,” she says.

She wipes her tears from her face.

“I’m here because you matter,” she says.

“You matter to me.

“You matter to your parents.

“You matter to your teachers.

“You matter to your friends.

“I want you to know that you matter.”

The students applaud, and when it is quiet again, LeAnn says, “I accept hugs, just so you know.”

And they line up on the way out, and hug her, one after another.

For suicide help

Teen Lifeline: (602) 248-8336 or visit teenlifeline.org

24 Hour Crisis Hotline: 1-800-784-2433